|

|

When D'ni was founded, the only source of light they had was a bioluminescent algae that Ri'neref wrote into the Age. It glowed brightly for fifteen hours and then gradually decreased in brightness to transition into a period of relative darkness for another fifteen hours, simulating the day-night cycle of their world of origin, Garternay. The light from the algae was enough to get around on the lake and river system inside the caverns, but the population couldn't always be near the water and their activities didn't stop at the end of the day when the algae dimmed. To provide living and working space, the D'ni had to dig tunnels and chambers in the rock around the residential and industrial caverns because there wasn't enough space to build very much in the open. This resulted in the majority of the living and working space consisting of excavated chambers. Since the algae wasn't enough, an artificial source of light was needed. Fortunately, the D'ni had one. It's unknown if it was invented early in D'ni history or if it was brought with them from Garternay, but the D'ni had knowledge of a substance that provided clean, efficient energy. It's unknown what the D'ni called it, but the DRC dubbed it either marbonium or marborium, depending on which notes are read. Marbonium could be combined with other substances and molded into spheres that made the marbonium stable. They made two kinds of sphere out of it. One was a ball a little larger than a man's hand that was safe to handle, but when connected to a machine provided a large amount of energy. Enough energy that they could power massive industrial machines with just one of the balls. The power balls had a fairly short lifespan when used, but could be stored for very long periods. This is a power ball that was providing energy to the D'ni tunnel drilling machine in the picture. The machine is called a worm, which I believe is ūcha in D'ni.

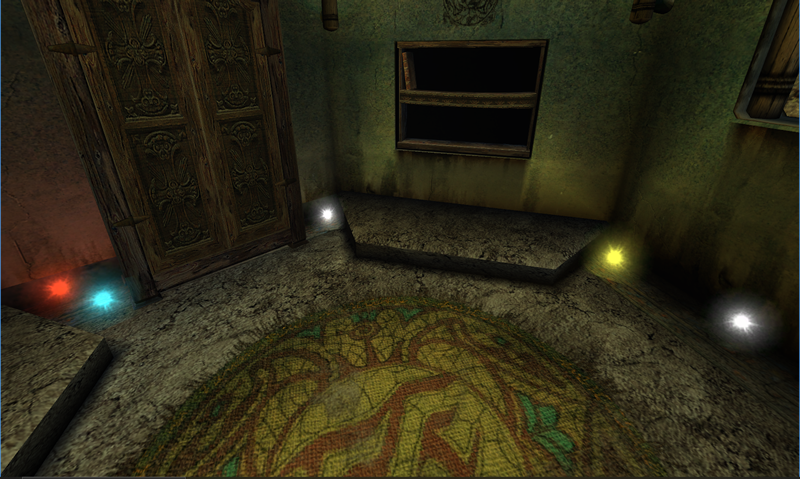

The other type was a transparent sphere that emitted light in various colors depending on the marbonium quality and where it was mined from. That type of sphere was called a dakotam, which means firemarble. Firemarbles couldn't be used to provide power to machines the way the power balls did, but in return they had a lifespan that could be measured in centuries. Firemarbles were typically mounted in lamps, helmets, or sometimes in hand torches. Since they were cool to the touch and posed no fire danger, they were the default light source used in the D'ni empire. Here is a collection of firemarbles, showing the range of colors they came in. White is the most common.

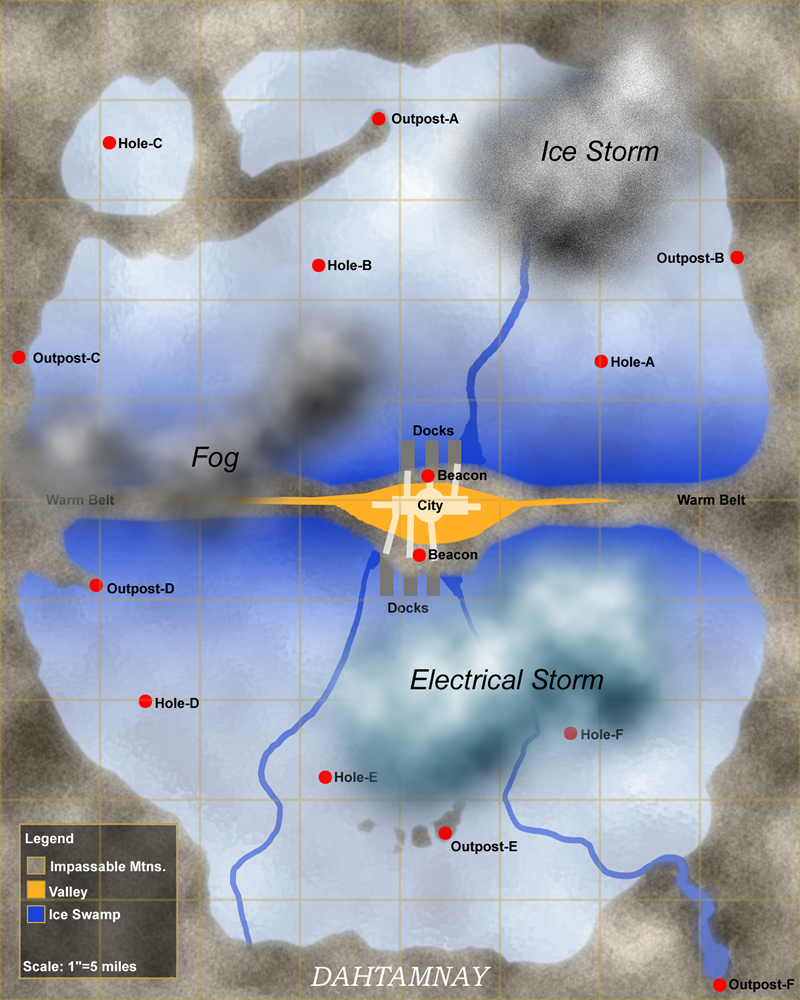

The linking book to the Age was discovered on September 26, 2000. Investigation of the Age was suspended a few days later by Dr. Ikuro Kodama, the DRC's chief engineer and expert in geology and structural integrity. The DRC members were interested in restoring Dahtamnay. If they could have reinstated the manufacturing of firemarbles, it wouldn't have just been useful in the caverns. They might have been able to make a profit selling them on the surface. With that in mind, they began to survey the Age. It didn't take long to discover just how hostile it was, and plans for restoration were suspended in September of the year 2000. The Age was not revisited before the DRC shut down the caverns due to lack of funding. In the year 2006, after having secured a financial backer, the DRC returned. As part of their renewed efforts, they took another look at Dahtamnay and voted to continue the suspension. Again, it was due to a recommendation by Dr. Kodama. On August 12th, 2006, he wrote a note that read, "Simply don't have the manpower. Recommending Suspend. Dr. K.". The caverns were closed a second time. Their backer had cut their funding before anything more could be done. The Age:The word dahtamnay is a contraction of dako-tam-nā, which means firemarble root. In this case, root implies a source of something. Dahtahmnay is an Age that was written by an unknown writer for the Guild of Miners to produce the materials needed for power balls and firemarbles. The world is said to have a very long day and night. Physically, the Age is made up of an icy sea in what might be a huge meteor crater. Running across the middle of the Age is a low mountain range. The mountains formed over a tectonic plate boundary, and the mountains are where the plate is being pushed upward by convergence with another plate. The collision causes volcanic activity below the surface. The heat generated by that activity is high enough to make the mountains much warmer than the sea around them. The sea is surrounded by virtually impassible cliffs that may be the edge of the meteor crater. This is a map of the Age as it was when the DRC surveyed it. The Holes are the locations of mobile drilling rigs left in the Age when D'ni fell.

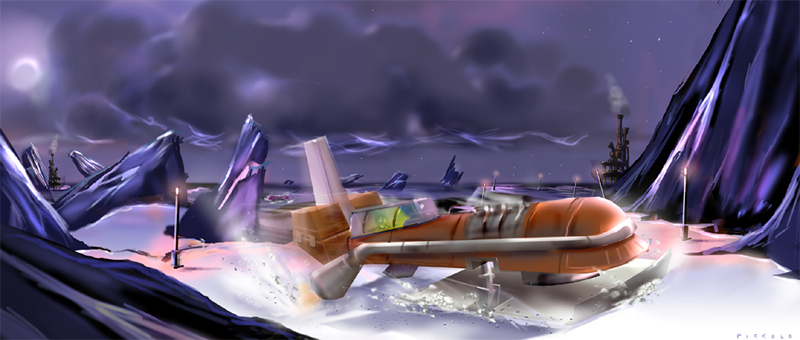

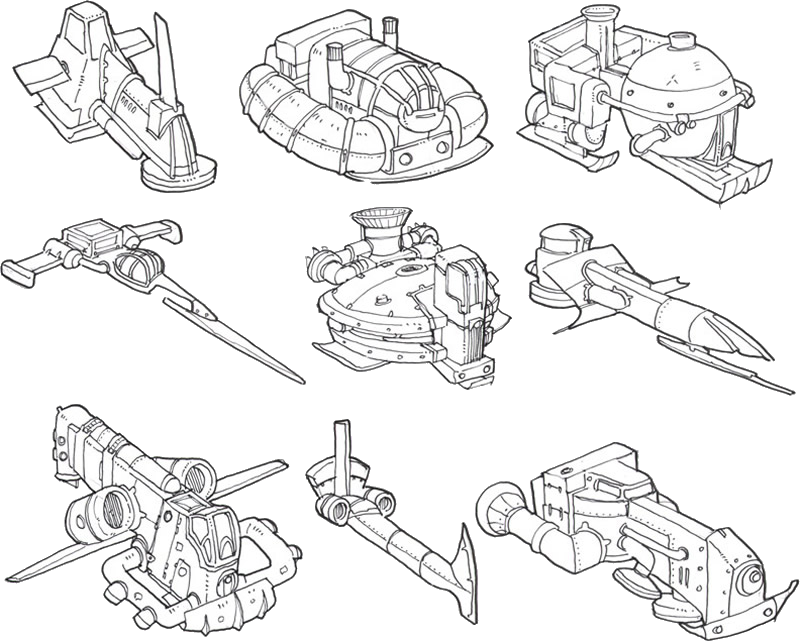

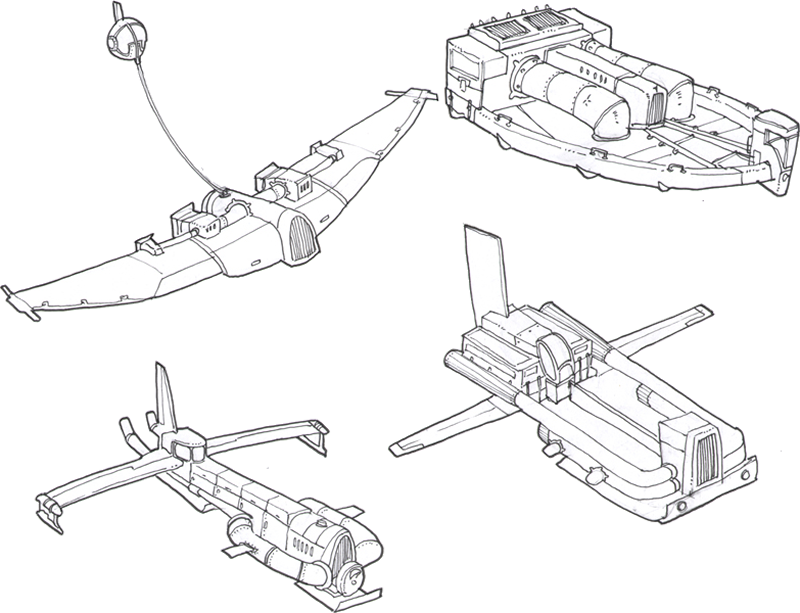

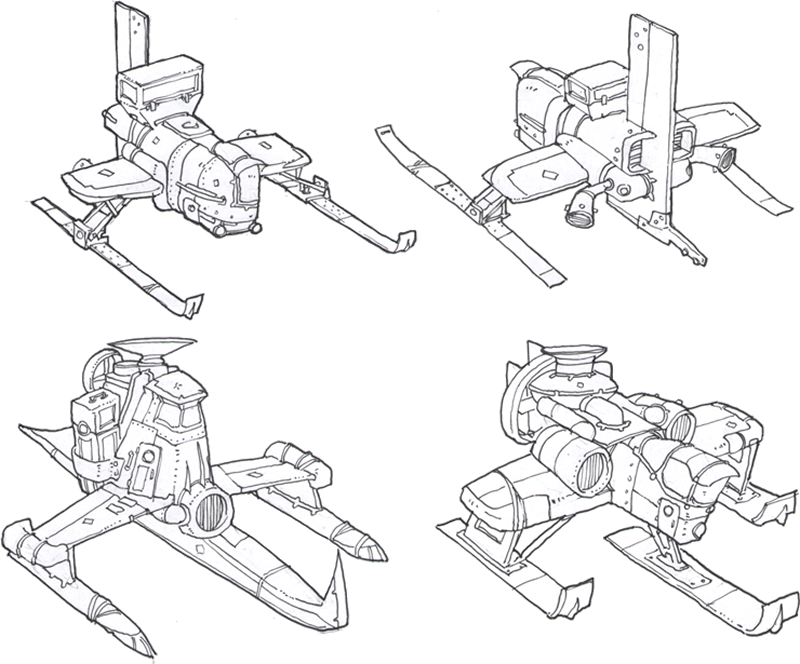

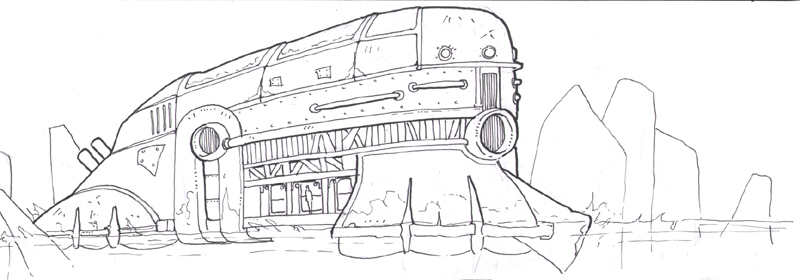

Marbonium had to be harvested from the depths of the sea, which are incredibly cold and deep. After being collected, it needed to be fused with another substance to stabilize it and release the latent energy it contained. The fusion required extremely high temperatures like those of a blast furnace. The process is described as extremely complicated, although no details are known of how it was done. The surface of the sea was called the tundra, and it was a no-man's land where anyone could go, but which was equally deadly to all. There were fast-flowing rivers filled with great icebergs cutting through the surface. Electrical storms blasted the tundra with chunks of hail larger than a man. D'ni records mention that there were rumors of gargantuan mammoth-like creatures somehow living in that frozen hell, but no images of one have been found. When speaking of the climate of Dahtamnay, warm was a relative term. Temperatures on the tundra could fall as low as -200 degrees Fahrenheit. The mountain range had temperatures that ranged between 0 degrees to 32 degrees Fahrenheit. Because of the extremely low temperatures, the ice atop the sea wasn't made of water. It was mainly made of various frozen gases. The exact composition of the ice isn't known, but notes hint that the sea itself contained frozen hydrogen deep below the surface. When the temperature in a given area rose above its boiling point, hydrogen from the deeps sometimes rose through cracks in the ice and formed pockets on the surface. This could be collected and used as fuel on the fly by vehicles traveling across the ice. A valley formed in the central mountain range, which the D'ni called the Crevice. It was where the D'ni built their industrial district. On the outer slopes of the mountains surrounding the Crevice were a series of wharves and piers that extended out onto the tundra. The industrial district's centerpiece was a massive building that resembled an oversized aircraft hangar. The building was oriented along a fault line that offered relatively easy access down to the volcanic zone deep below. The D'ni constructed huge pipes the diameter of entire rooms to tap into underground heat. The hot air piped up was used to produce steam and was blown through other pipes to buildings near the docks outside the valley. The building was said to have two levels. The upper level housed steam generators to produce electricity for the rest of the industrial district. The lower level had an area called a ready room where Guild delivery pilots waited for their next assignment. The ready room had maps where drilling rig locations were marked daily. Weather, terrain and market reports were collected by the Guild and posted on information boards. The Guild operated the drilling rigs, so their ready rooms always had the most accurate information about them. There were two other ready rooms located in the Crevice along with the main one in the hangar. Elsewhere in the building was the production facility where power balls and firemarbles were made. Outside the industrial district one could find two kinds of facilities. The first were the mobile drilling rigs, and the second were outpost towns set on islands and spurs of ground around the edge of the sea. The outposts had informal ready rooms in pubs that did what they could to mimic the Guild ready rooms in the Crevice. The outposts were unofficial and not associated with the Guild of Miners. Over the years, a number of merchants and mechanics had become frustrated with Guild laws and restrictions on what they could do, and established the outposts as a place where one could find services that the Guild would not provide. These services included specialist mechanics who performed unique upgrades and modifications that were unavailable to Guild members. In fact, Guild members were not welcome in the outposts except in a life-threatening emergency. One mechanic that was mentioned in documents found in the Age was a man named Yuta. He was said to be the go-to guy if you wanted a grappling hook maneuvering mod installed. It was also noted that if you didn't have a gift of fresh steaks for him when you showed up, he wouldn't give you the time of day. Travel and working conditions on the tundra were extremely hazardous. Not only did the people who ventured out onto it have to deal with bitter cold, there were near-permanent ice, sleet, hail and electrical storms awaiting the incautious. Industry and Life:The Age wasn't just home to people who worked with Guild of Miners. There were people who lived in the Age in ice-block homes around the outposts. They provided non-Guild services for the people who worked with the mining operation. There were even eco-tourists who visited the Age just to see the extreme climate. But for the majority of the people who went there, life revolved around the mining and transportation of marbonium. It's said that there were three grades of it, low, standard, and clean, with the better grades having longer half-lives. Mobile drilling rigs called excavation platforms wandered across the tundra searching for traces of marbonium. When they detected a deposit, they would stop and set up for operation. Like an oil drilling rig on Earth, the platforms would auger deep through the ice and into the sea beneath, adding sections of pipe to the drill until they finally reached the deposit. Then the marbonium would be pumped to the surface. Once the deposit was exhausted, the platform would move on in search of another. When marbonium was raised to the surface, a race against time began. Away from the frigid temperatures and high pressures of the depths, it has a very short half-life and had to be transported to the factory as quickly as possible to be processed into a stable form. Sleds:The answer to the problem of rapid transport was a specialized vehicle called a sled. Sleds were fast. Base model sleds were capable of reaching two hundred and fifty miles per hour, and properly customized ones could reach five hundred miles per hour. Sleds could pull large tanks filled with marbonium from the drilling rigs to the factory docks in the industrial district. The faster the sled, the farther it could go to pick up a load and take it to the Crevice before it became worthless. The sleds had hermetically sealed cabins for the pilots, who only left the cabin when in port. Opening up a hatch or door was suicidal when out on the tundra. Because of that, all sleds came equipped with a linking book to a safe Age on a small shelf where it could be touched by the pilot's chin, an action known as a chin-out. If a sled was wrecked or became stuck, a chin-out before the cabin air froze was the only option for survival. Sled pilots were called runners, and came in two basic types, public and private. Both were paid the same way. Runners earned nurē (pronounced nuh-ree), the base D'ni currency, on a sliding scale that was calculated by how much marbonium they delivered, how fresh it was, and what grade it was. Public runners had Guild taxes deducted from the payout before they received it. The payout was a transfer of funds to the runner's prådnurētē, which loosely translates as money stone. Money stones were the D'ni version of what we call smart cards. Public runners were members of the Guilds of Miners, and had a rank system that rated them according to their job performance. Licensed by the Guild, they paid a guild tax on their operations but in return were loaned Guild authorized sleds and had access to Guild approved modifications. They were also guaranteed a replacement sled if through no fault of their own their assigned sleds were damaged or destroyed. They also had access to better facilities and priority information about which drilling rigs were going to need runners and what the weather conditions were. However, being a Guild runner wasn't a guarantee of advancement or high profits. The Guild expected their runners to be quick, safe and efficient. Poor results would see the rank of the runner lowered and important runs would be assigned to others. Private runners were adventurers who linked to the Age to try to make quick fortune. Since they were unlicensed, they had to purchase their own sleds and customized them when they could afford to. Because they were unlicensed and not Guild members, they had no insurance and were second in line for news about the rigs and weather unless they paid for the information. However, it also meant they didn't have to pay Guild taxes, could keep whatever money they earned, and could take risks the Guild runners were forbidden. Private runners were the rebels of Dahtahmnay, and had their own hangouts in outpost town pubs where they waited for jobs to be announced. They were risk-takers who customized their own sleds and were noted for using modifications that sometimes worked and sometimes didn't. When they did, the results could be outstanding. In the end, the Guild really didn't care who delivered marbonium or whether that person was a Guild member or not. If a private runner could deliver marbonium fast and in good condition, he or she was paid the same as the public runners. Sleds weren't the only vehicles on Dahtahmnay. Another type was huge privately owned vehicles called trucks that carried people and supplies between the industrial district and the outposts. The Service Industries:Backing up the runners were various support organizations. These included hotels, pubs, restaurants, stores, laundry services and all the other things a person needs to live. But the mining industry had several that existed mainly for their benefit. The most important was the weather service. Weathermen on Dahtahmnay first issued a report to the Guild of Miners, who passed it on to public runners via monitors and displays in the Guild ready rooms. After they'd given the reports to the Guild, they passed them on to a broadcaster who read the reports over a public radio station. The weather broadcast was played over speakers in the private runners' outpost hangouts and could be picked up via radio sets built into their sleds by runners who were out on the sea. However, there was a back door to the weather service and a private runner could obtain the reports almost as soon as the Guild did if they were willing to pay for them. Many did, since up to date weather information could be the difference between life and death. The weather reports gave detailed information about wind direction and strength, the location of hydrogen gas pockets which runners used to replenish their fuel tanks, where active storms were, ice conditions and anything else that might aid the runners in completing their contracts and survive the climate. Another important service was provided by traffic controllers whose job was to direct runners around icebergs and rivers, and to provide them with the most efficient routes. The ice atop the sea was constantly changing, and without traffic controllers keeping an eye on the big picture, a runner could get lost, run out of fuel, or get into an accident that destroyed his sled. It's not stated, but I suspect that the traffic controllers were impartial and gave directions freely to anyone out on the tundra. After a chin-out, there were two options for the unfortunate runner to try to recoup some of his losses. Assuming the sled was recoverable, he or she could call for a Guild salvage barge. The barges were a Guild-run reclamation service that could be called upon by any pilot who had to chin-out. It was free for Guild runners. Private runners had to pay a small service fee. This was quite generous of the Guild, but there was a drawback. There were a small number of salvage barges, and there was always a waiting list. I'd place a bet that public runners were given first priority. For runners who didn't want to deal with the Guild salvage service, there were private merchants both in the Crevice and at the Outposts who ran their own salvage operations for wrecked sleds. They cost more than the Guild barge, but the runner got faster service for the money. The private salvage services would get right on the job, and the runner would be back in business in relatively short order. Illustrations:Here is an example of a runner's sled.

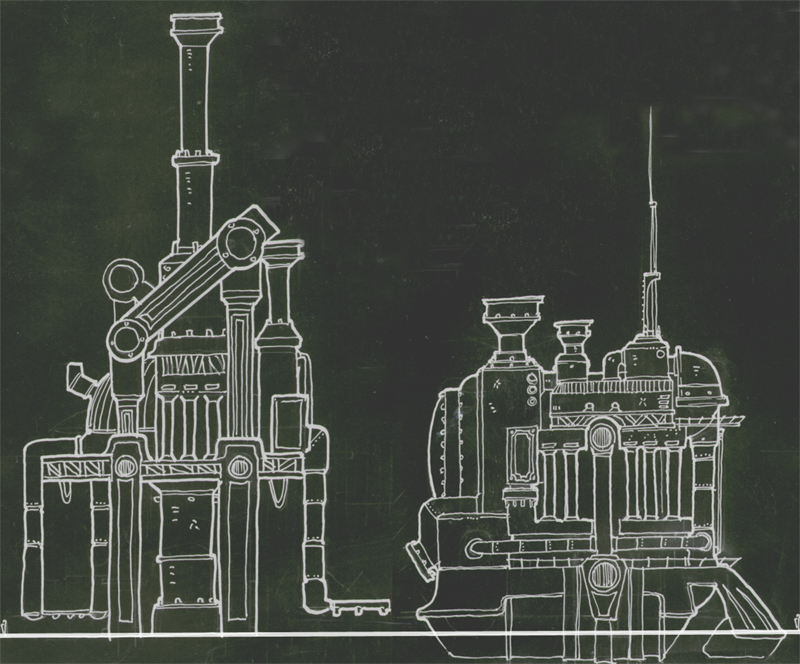

These sketches show designs for two of the mobile mining rigs.

This is a sketch of what may be a street in a outpost.

This series of sketches show just how varied sleds could be. Every runner and mechanic had their own ideas about what would work best on the tundra, and customizing was a fine art among them.

This is an example of a truck used to transport people and cargo between outposts and the industrial district.

|

Myst, the Myst logo, and all games and books in the Myst series are registered trademarks and copyrights of Cyan Worlds, Inc. Myst Online: Uru Live is the sole property of Cyan Worlds Inc. The concepts, settings, characters, art, and situations of the Myst series of games and books are copyright Cyan Worlds, Inc. with all rights reserved. I make no claims to any such rights or to the intellectual properties of Cyan Worlds; nor do I intend to profit financially from their work. This web site is a fan work, and is meant solely for the amusement of myself and other fans of the Myst series of games and books. |